Blog

-

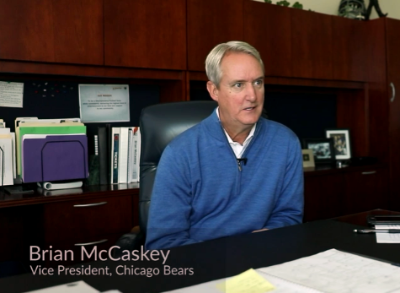

Bears’ Brian McCaskey on hearing loss: ‘Technology has really saved me’

14 Nov , 2017

14 Nov , 2017

Bears’ Brian McCaskey on hearing loss: ‘Technology has really saved me’

Brian McCaskey couldn’t watch, and it had nothing to do with the Bears losing 31-3 to the Giants in an NFC divisional playoff game.

McCaskey never made it out of his New York hotel room, with a sudden attack of vertigo rendering him dizzy, disoriented and helpless. Doctors eventually diagnosed McCaskey, the second-youngest son of Ed and Virginia McCaskey, with Meniere’s disease, an inner ear disorder that includes ringing sounds and hearing loss. The bouts limiting the function of McCaskey’s right ear continued sporadically as visiting emergency rooms and trying different medications became a regular part of life.

“With each attack I’d lose more hearing,’’ McCaskey, a Bears vice president, said.

One of the most memorable episodes happened Jan. 23, 2011, when the Bears played the Packers in the 2010 NFC championship game at Soldier Field. After arriving at the stadium, McCaskey began to sweat profusely and feel nauseous. His blood pressure dropped and the debilitating symptoms made him unable to stand so he laid on the floor inside the Bears locker room until his world stopped spinning. George McCaskey, now the Bears chairman, stayed at the side of his ailing younger brother as the team their family owned played outside for a Super Bowl berth.

“He gave up watching the game,’’ Brian said in his first interview about his hearing loss.

The McCaskeys and close friends knew of Brian’s ear issues but fiercely protected his privacy and hoped for the best. Then came the worst when Meniere’s struck again around McCaskey’s 50th birthday.

“I woke up one day deaf, literally, in my second ear,’’ said McCaskey, 57, who’s on the advisory board of the HearStrong Foundation, which recognizes the accomplishments of people who overcome hearing loss. “The analogy I use is you can fly an airplane on one engine but when the other one conks out, you have problems. I had problems.’’

McCaskey’s biggest problem: Now, neither ear worked.

Defined medically, McCaskey suffers from a sensorineural loss — damage to the hair cells in the sensory hearing organ called the cochlea. Addressing the issue seven years ago after he lost hearing in his good ear required surgery called endolymphatic sac decompression and shunt insertion, a procedure deemed necessary when conservative treatment fails. It involved going into the part of the skull just under the brain to create a drainage portal.

“The swelling after the surgery initially made everything worse but, luckily, after awhile it got better,’’ McCaskey said.

Recovery included a new reality — a much quieter one.

“My hearing was gone, and what’s gone is gone — it’s not coming back,’’ McCaskey said. “Birds can restructure their hearing. Fish can restructure their hearing. Humans cannot. Once there is hearing damage to the cochlea and the hair cells inside the cochlea — a structure the size of the tip of your pinkie — there is no going back.’’

Nowadays, McCaskey functions with little fuss by insisting on buying the hearing-aid equivalent of the iPhone X — the Widex Beyond 440, a state-of-the-art device he found with help of audiologist Kathy Highhouse in Hinsdale. He prefers small meetings and carefully picks his seat so the skilled lip-reader can watch the main speaker enunciate. He avoids Halas Hall’s dining area because it gets too loud. He knows by now who the soft talkers are in the building and whose inflections he appreciates.

His teenage daughter, Kelly, talks in a high voice that causes no trouble. His son, Keegan, a freshman at LSU, speaks deeper, in tones that can cause difficulty. As for his wife, Barb, McCaskey kidded he still has selective hearing like many husbands.

“If she’s trying to talk to me from the other room, it’s not going to go very well,’’ he said.

Except for in bed or in water, McCaskey constantly wears his hearing aids, which look like the IFB earpieces upon which television anchors rely. He never uses the phone on his desk but his cell-phone beams a signal through his earpiece so he can make and take calls. He also has a mechanism that allows him to hear TV shows and church sermons spoken into a microphone, as if he was listening to an iPod.

The music buff still goes to shows and concerts, extremely grateful for the technological progress that allows him to enjoy his favorite songs. After receiving a newer, improved set of hearing aids recently, McCaskey found himself home alone ordering Alexa from Amazon: “Play James Taylor.’’

“I sang my heart out in the kitchen for about two hours and while I appreciated it, I’m not sure my dog did,’’ McCaskey said. “Technology has really saved me.’’

The hearing aids fit in McCaskey’s ears seamlessly enough that many strangers never notice. At a Super Bowl XX reunion, for example, former Bears fullback Calvin Thomas was speaking too softly for McCaskey to pick up his voice.

“I said, ‘I’m sorry, Calvin, I can’t understand what you’re saying because I have hearing aids,’ ’’ McCaskey said. “He said, ‘You do not!’ So I took them out and showed him.’ ’’

McCaskey’s increased comfort discussing a condition he once considered an “old person’s disease” compelled him to help others cope with the type of stigmas or self-consciousness he overcame. Enter Ed Keller, the president of EarQ and HearStrong, who met McCaskey several years ago through late Patriots and Syracuse coach Dick MacPherson when he was looking for a speaker with NFL ties.

“Brian stepped forward and said, ‘I want to get involved and I want to get my hands dirty,’ ’’ said Keller, in town to give away a scholarship and raise awareness Monday night downtown at the foundation’s banquet.

The program includes a speech by a member of Chicago’s first family of football who might appreciate the roar of the crowd Sunday against the Packers more than any of his relatives.

“Being part of the Chicago Bears front office gave me a platform to try to help others,’’ McCaskey said. “I have 48 million brothers and sisters who have experienced hearing loss. It touches everybody, so just encourage people to get help and break that stigma that it’s for older people. It’s not. Reach out, get help and take care of your hearing.’’

Message received, loud and clear.

Source: chicagotribune.com

Image credit: chicagotribune.com