Blog

-

Hearing has been partially restored in deaf lab mice using a novel therapy

3 Jul , 2018

3 Jul , 2018

Hearing has been partially restored in deaf lab mice using a novel therapy.

A small molecule of a drug has been successfully used to treat an inherited form of hearing loss in laboratory mice. The study was conducted by researchers at the University of Iowa, Iowa City, and the National Institutes of Health’s National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD). It could mean that a new treatment option could be underway for people with this form of deafness. The results of the preliminary study were published in the latest issue of the journal Cell.

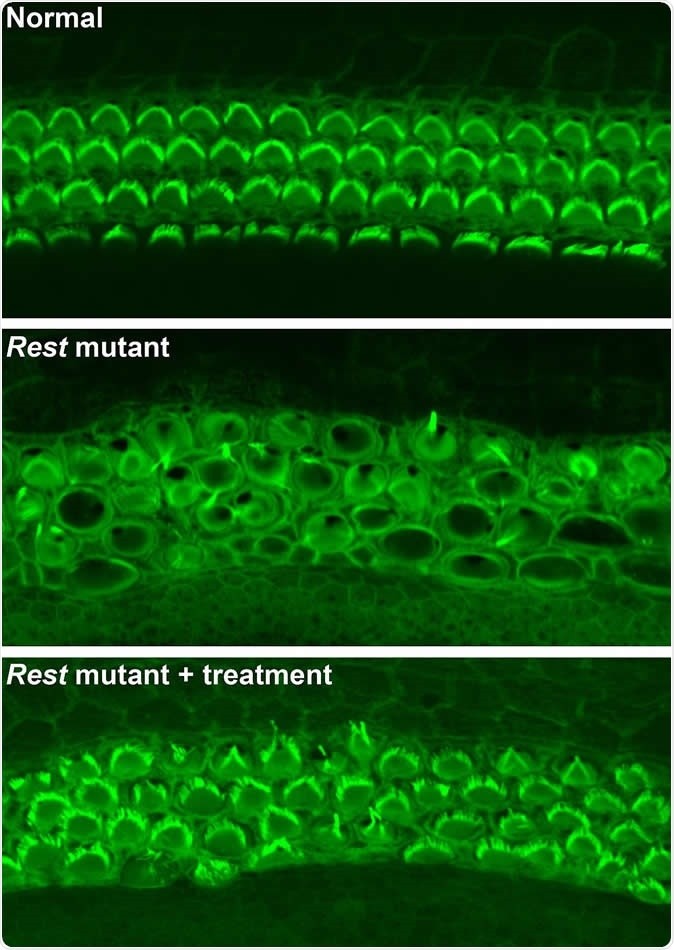

The team of researchers notes that using small molecule drug, this form of deafness called DFNA27, could be partially reversed. Thomas B. Friedman, chief of the Laboratory of Human Molecular Genetics at the NIDCD and a collaborating author of this study explained that this novel therapy could restore hearing at lower sound frequencies and save some of the “sensory hair cells” within the inner ear. He said that they were hopeful that more small molecules could be used in future to treat other forms of progressive deafness.

Friedman and Robert J. Morell from NIDCD, in their earlier study a few years back looked at the genetic basis in an inherited form of deafness. The family members and blood relations of the family called LMG2 carried a dominant gene which when passed on to the children caused progressive hearing loss among them. In the present form of hearing loss the team had found that there was a genetic mutation on chromosome four called DFNA27. There are quite a few genes at the place which when altered, could be affecting the hearing.

Botond Banfi and Yoko Nakano, University of Iowa, who led this current study found that mice with DFNA27 form of progressive deafness had a Rest gene (RE1 Silencing Transcription Factor). This gene is important because it regulates the sensory cells within the ear that are vital for hearing. In humans the counterpart of this Rest gene is found in the DFNA27 region. Once the location and function of this gene was better understood the teams from Iowa University and NIDCD teamed up to see what could modulate the gene and help improve the deafness.

To create the mice model of DFNA27 deafness, the team deleted a portion (called exon 4) of the Rest gene. This manipulation led to the death of the sensory hair cells within the mice inner ear rendering them deaf. Similar mutation changes in this region were found in the LMG2 family as well. Once this exon 4 region was inserted into the REST mRNA, explained Banfi, it switches off the REST protein. This in turn allows many of the genes to switch on and these latter genes help in survival of the sensory hair cells and allow the mice to listen better.

For this study the team thus used mice that had modified genetic code without the exon 4. They served as models for DFNA27 deafness. The REST protein normally suppresses the genes by a method called histone deacetylation. The team now used a small molecule of a drug that could block the process of histone deacetylation and thus turn off the REST. Switching off REST allowed a partial return of hearing they noted.

Andrew J. Griffith, scientific director of the NIDCD said that the results of this study show the value of understanding the “molecular mechanisms that underlie inherited forms of deafness.” “By following these genetic leads, we find novel and unexpected pathways that can, in cases such as this one, uncover unexpected potential treatment strategies in humans,” he said.

Source: cell.com, Dr Ananya Mandal, MD

Image credit: Yoko Nakano, Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, Originally published in Cell